Envy is one of those feelings seen by some as a “negative feeling,” like anger or sadness. The Bible includes envy or coveting among the Ten Commandments of things not to do, in obeyance to God.

Envy is one of those feelings seen by some as a “negative feeling,” like anger or sadness. The Bible includes envy or coveting among the Ten Commandments of things not to do, in obeyance to God.

As a therapist, however, I do not subscribe to the idea of positive/good or negative/bad feelings. Feelings simply are. They are part of the human experience, the range of emotions we experience in life. Envy is no different. It is human to wish we had the advantages, accomplishments or relationships that another or others may have. For example, trustworthy friends, children, good health, a high-paying job, a slimmer body or a partner. We feel envious. When a woman with no children has a miscarriage she is likely to find it hard, soon after, to see women pushing a newborn or toddler in a stroller, harder still a friend with a child. She is envious, wishes she too had a child, and the pain of her recent loss is exacerbated by being around a friend and her child. She may want to limit time around them until it isn’t so painful. If she and her friend are close and confide in each other, she may be able to share her feelings and need to limit their contact for a period of time. A true friend will understand. S/he/they may inquire if there might be any contact or action that the friend would find supportive, and if not, accept the friend’s need as part of their friendship.

It is possible to feel both envy and happy for someone we have a mutually caring relationship with who gets something we desire, say an article published, a Ted-X talk or a better job. We may be able to acknowledge it with them and have it absorbed. We may be able to laugh about it. We may hear from that person about a time or times s/he/they may have envied us. There is no venom, and that is what makes it possible. I am blessed to have a dear friendship with this capacity.

There’s another practice I’ve found helpful when I’m envious of someone in regard to a particular attribute or gain they have. I remind myself that I don’t get to extract a particular thing(s) from that person’s life, that it comes as a package of the person’s entire life. Often, it’s clear to me that trading the entirety of my life with that of another is not desirable to me and the air in envy deflates.

Where things can get funky is when resentment, anger, worthlessness and devaluation get triggered with the envy. The latter is reflected in the phrase, “You think you’re better than me,” or another common one in our community, “She thinks she’s all that.” It is hard to be happy for someone when their gain has triggered a sense of worthlessness and devaluation in us, one that for marginalized populations has been planted and well-nurtured. Sadness, anger, even rage can rush in. But rather than judge such feelings as “bad,” I suggest we accept them when they arise, and hold ourselves compassionately with them, that we have this pain. This is part of what I understand as self-love.

It is also important that we reflect on them, rather than let anger rip. Has the source of our envy devalued us or treated us like we are worthless? If so, is the devaluation persistent or a rare mistake that has been/or can be repaired? If it’s been persistent, we can ask ourselves what has allowed us to be in such a relationship and if we want to continue. Does some part of us feel we don’t deserve better or is afraid of better? Are we constrained financially to stay? It is also important to consider whether we are projecting a sense of devaluation on the other, an expectation of such, rather than it being a reality. Sometimes people are thinking and acting like they are better than another, and sometimes, we are seeing them that way or expecting them to be that way because of other experiences we’ve had. Sometimes, both can be true.

In other words, we can allow our sadness or anger to help us look inward to explore what is going on and what our options are for dealing with these feelings.

If upon reflecting we see that the person we’re envying has not treated us badly, then other questions can arise. Does s/he/they deserve our anger or resentment? Who or what has nurtured a sense of devaluation and worthlessness in us? It could be family member(s), teacher(s), other so-called friends or the many tentacles of racism, sexism, classism, heterosexism infused in our systems of thought, language, imagery, behavior and institutional practices. Anger, rage, and grief are all appropriate feelings for such practices, as well as how devaluation lives in us. So often, those closest to us become the target for this anger or rage, beyond what they are accountable for. This exacerbates the pain in our communities of friendship, family, and neighborhood. Anger does indeed need to be expressed, but how it is done is critical. Though we may be vulnerable to blasting another in the throes of our rage-pain, it has its limits as a general and singular response.

If we have trusted friends who are not the source of our envy and resentment, and who will not judge our feelings or fan the flames for us to take rash action, it can be helpful to share our feelings with them, both the anger and the hurt. They can help validate our reaction, raise questions and brainstorm possible actions to take, and when.

Envy combined with anger/rage is high octane fuel.

That is why it is valuable to hold them compassionately, learn from them, and use them thoughtfully. The mission we put them to matters. I for one believe in dedicating the rage to actions of healing and social justice.

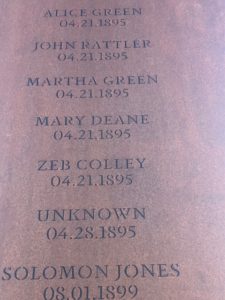

My eyes behold slab after slab hanging above me, organized by State, by counties, engraved with names and dates of death. Columns and rows stretch ahead of me, suspended from on high the length of the four, open sides of the structure. The list of names on some slabs is very long, telling me the terror in those counties moved especially thick through the lungs of my People there. Even sadder than seeing that multiple family members were hanged in a county is the unknown appearing again and again sandwiched between those named. It’s as though they have been doubly disappeared from the face of the earth.

My eyes behold slab after slab hanging above me, organized by State, by counties, engraved with names and dates of death. Columns and rows stretch ahead of me, suspended from on high the length of the four, open sides of the structure. The list of names on some slabs is very long, telling me the terror in those counties moved especially thick through the lungs of my People there. Even sadder than seeing that multiple family members were hanged in a county is the unknown appearing again and again sandwiched between those named. It’s as though they have been doubly disappeared from the face of the earth. I stand still, acknowledging the lives, the fault lines cut through families and communities by this macabre murdering. I stand in a mud of sorrow and a rain of gratitude, the Memorial and my presence a testimony that these lives mattered. When I eventually turn right along the next section, there is a wall of water flowing down, the strength of its softness holding me alongside the hanging rectangles that continue.

I stand still, acknowledging the lives, the fault lines cut through families and communities by this macabre murdering. I stand in a mud of sorrow and a rain of gratitude, the Memorial and my presence a testimony that these lives mattered. When I eventually turn right along the next section, there is a wall of water flowing down, the strength of its softness holding me alongside the hanging rectangles that continue.

I am also going to see the Lynching Memorial and The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Incarceration, both in Montgomery, Alabama. When I was growing up, my Mom and I took a 30 minute drive to Montgomery from time to time to shop for clothes, boycotting the White stores in Tuskegee. Not that they had any clothing retail worth walking into. But there in Montgomery, we encountered the Colored and White water faucets and the saleswoman with the drawl who said “Thank you Johnnie” to my mother, a familiarity that served up White supremacy.

I am also going to see the Lynching Memorial and The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Incarceration, both in Montgomery, Alabama. When I was growing up, my Mom and I took a 30 minute drive to Montgomery from time to time to shop for clothes, boycotting the White stores in Tuskegee. Not that they had any clothing retail worth walking into. But there in Montgomery, we encountered the Colored and White water faucets and the saleswoman with the drawl who said “Thank you Johnnie” to my mother, a familiarity that served up White supremacy.

President ’45’ is only the pus head, because the infection is widespread among our government representatives — silence while children are poisoned in Flint, former DEA agents now on pharmaceutical payrolls, former DEA folks turned draftee(s) of legislation to hamstring prosecution of pharmaceutical companies that pushed opioids like a goldrush, lobbies for corporations that want more freedom to poison our water, air, earth, to control what beans get planted, to keep us from knowing what food is genetically modified, to flood us with guns. Money, money, money, money — above all else. I believe what I see, no shame among them.

President ’45’ is only the pus head, because the infection is widespread among our government representatives — silence while children are poisoned in Flint, former DEA agents now on pharmaceutical payrolls, former DEA folks turned draftee(s) of legislation to hamstring prosecution of pharmaceutical companies that pushed opioids like a goldrush, lobbies for corporations that want more freedom to poison our water, air, earth, to control what beans get planted, to keep us from knowing what food is genetically modified, to flood us with guns. Money, money, money, money — above all else. I believe what I see, no shame among them. I’m soon off on a family trip to Savannah, Georgia. I’ve never been there before, but have heard it’s beautiful, similar to Charleston, and a former port where Africans who survived the Middle Passage were delivered. When I google Savannah for things to do, there is no mention of this port as a gateway to slavery. Among the suggested top ten things to do, nothing related to slavery appears. I must google Savannah and slavery. That is where I find reference to a 2014 article in the Atlantic detailing one of the largest, if not the largest, auction of enslaved men, women and children in the U.S. It happened in 1859 in Savannah. It was known as The Weeping Time, and it is evident who named it so.

I’m soon off on a family trip to Savannah, Georgia. I’ve never been there before, but have heard it’s beautiful, similar to Charleston, and a former port where Africans who survived the Middle Passage were delivered. When I google Savannah for things to do, there is no mention of this port as a gateway to slavery. Among the suggested top ten things to do, nothing related to slavery appears. I must google Savannah and slavery. That is where I find reference to a 2014 article in the Atlantic detailing one of the largest, if not the largest, auction of enslaved men, women and children in the U.S. It happened in 1859 in Savannah. It was known as The Weeping Time, and it is evident who named it so.